Do Physically Active Children Attain Higher Academic Achievement?

Physically active youngsters seem to have an advantage when it comes to academic achievement. They retain more information in memory to process actions and decisions. They learn, focus and manage their impulses better than others. And regions of their brains critical to mental performance appear to be larger and to connect better with one another.

In short, many scientists who study children believe that kids who are physically active learn more quickly and efficiently and behave better.

The research exploring these benefits is stronger for children ages five to 13 years than it is for younger children or adolescents. And although the impact of physical activity on learning is significant, its influence on behavior may be even greater.

“The scientific evidence continues to build—physical activity is linked with even more positive health outcomes than we previously thought,” according to the introduction to the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition.

Who benefits—and how?

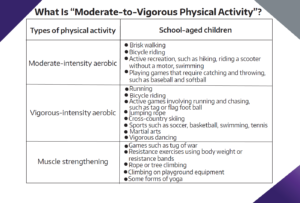

The Physical Activity Guidelines recommend that children and adolescents ages 6 through 17 years do at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. In the Guideline’s Scientific Report and other recent reviews, scientists analyzed the impact of exercise on the brain health of children. In analyses of dozens of studies, they found:

- Children benefit from physical activity that is moderate to vigorous in intensity. The benefits include improvements in how they learn, remember, pay attention and reason, including how they perform on academic achievement tests. The benefits extend to tests that involve processing speed, memory and the ability to plan, organize and complete tasks.

- Other improvements include managing emotions and ADHD symptoms. Physical activity appears to help children who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) manage impulsive or inappropriate responses and emotions.

- Children who exercise appear to have bigger brains that function better. “A growing body of evidence… suggests a relationship between vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activity and the structure and functioning of the brain,” noted the authors of the Institute of Medicine’s 2013 report, Educating the Student Body.

- A variety of activities may fuel these benefits. They include brisk walking, cycling or dancing, playing games such as tug of war or tag, or participating in organized sports such as basketball and soccer. (See table.)

- Children ages five to 13 benefit. There is not yet enough evidence to say whether physically active children less than age five or adolescents ages 14 to 18 experience similar benefits. Benefits are not increased or lessened by a child’s social or economic situation, race, ethnicity or body weight.

- A brief bout of physical activity yields temporary improvements. The optimal amount of school-related physical activity seems to be sessions lasting 11 to 20 minutes. These may occur during physical education class, recess or active classroom lessons.

- Routine physical activity yields longer-term benefits. Although improvements are initially temporary, some become long-lasting when physical activity is an ongoing part of a child’s routine.

Routine physical activity is potentially life-altering

Although these findings are based on the best available research, the authors of these reports make it clear that their conclusions could change with future research involving more children or better and different methods.

Nevertheless, write the authors of physical activity guidelines Scientific Report, “These effects are found across a variety of forms of physical activity… and… across a variety of experimental designs and cognitive outcomes.”

Success in school often heralds a child’s fortunes later in life. “[A]cademic achievement is a predictor of future job opportunities and adult health,” note the IOM authors. That means the link between physical activity during childhood and intellectual and academic attainment is potentially life altering.

Source: Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition, page 51