Do Team Sports Offer Health Advantages that Other Activities Do Not?

Children and adolescents move, play and engage in sports in lots of different ways. They skip rope, throw balls, jog alone or compete on teams against one another—all healthy ways to be active. In recent years, researchers have begun to explore whether some of these activities are more closely linked than others to specific health benefits over time. One question of keen interest to scientists and parents is, “Do team sports offer health advantages that other activities do not?”

The paybacks from being physically active are far-reaching; they can include boosts in muscle strength and heart and lung health, protection from childhood chronic diseases such as diabetes or asthma, and improvements in thinking, focus and academic achievement. Athletes participating in individual sports such as track and field or swimming experience many of the same physical, social and mental health benefits as athletes playing basketball, soccer or other team sports.

Yet team sports may provide psychological and social benefits that individual sports or exercising alone do not. “Team sport seems to be associated with improved health outcomes compared to individual activities, due to the social nature of the participation,” according to one review of the science.

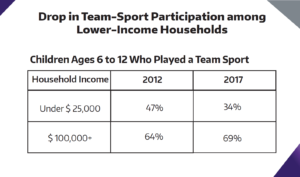

As the research on team sports has advanced, however, the participation gap between higher- and lower-income families has widened. A recent survey indicates that children from lower-income families who might enjoy the benefits of team sports are being squeezed out by the steep cost of participation.

The benefits of team sports

The research on team sports shares some common themes. One is that team sports appear to improve the social and mental health of young participants.

A 2013 analysis reported on two decades of studies that followed children and adolescents who played sports. It found that team athletes felt greater self-esteem, less fearful in social situations, less socially isolated and more socially accepted compared to their peers who participated in individual sports or no sport. In one study, increased self-esteem in adolescent urban girls was linked to a sense of achievement and competence in their sport. In another study, team athletes reported lower levels of suicidal thoughts, suggesting caring adults and teammates may form a protective social network.

A second, related theme is that some of the social and mental health benefits of playing team sports in childhood and adolescence seem to extend into early adulthood. In a series of papers, Canadian researchers analyzed responses from more than 800 boys and girls who completed health surveys every three months in the 7th through 12th grades. In the final survey taken three years after they left high school, young women and men who had participated in any school sport—individual or team—reported lower depression symptoms and stress and enhanced mental health.

In a follow-up analysis, the researchers tried to tease out whether certain types of sports seemed to account for reduced depressive symptoms in later years. They found that team sports appeared to protect athletes against depressive symptoms in young adulthood, while individual sports did not. If other studies arrive at similar results, the authors wrote, “strategies should be implemented to encourage and maintain team sport participation during adolescence.”

In research conducted since then, people exposed to childhood adversity completed health surveys over the course of 20 years, from childhood to early adulthood. As children they suffered physical or sexual abuse or emotional neglect or lived with a parent who misused alcohol, went to prison or was single. Men and women who played team sports as adolescents were significantly less likely to develop anxiety or depression in their 20s and early 30s than their peers who did not play team sports.

“The wins and losses of sports teach the emotional dexterity required for success in life, including resilience,” suggested the authors of an editorial in JAMA Pediatrics that accompanied the study’s publication. (See related article, Team Sports in Teens May Fortify Mental Health of Adults who Suffered Childhood Neglect and Abuse.)

This research does not mean that team sports are a cure-all for social and mental ills. For starters, some of the links connecting team sports to improved health are weak. The results of the studies do not all agree. And the study methods are generally not capable of pinpointing team sports as the reason for improvement. It’s possible, for example, that factors the researchers did not measure accounted for some of the improvements. It’s also possible that kids who are attracted to team sports are mentally and socially healthier than other kids to begin with, and that these characteristics follow them into adulthood.

Increasing opportunities for physical activity and sports

If indeed team sports help to inoculate children and adolescents from mental health problems years into the future, it will be important to maintain and expand access to youth sports for anyone who might benefit. However, the booming youth sports industry has contributed to a perilous gap between higher- and lower-income families. Personal coaches, high participation fees, expensive facilities and team travel drive up the cost of competing.

According to the State of Play 2018 report, 69% of children from households earning $100,000 or more played a team sport in 2017. Only half as many children (34%) played team sports if they lived in lower-income households earning under $25,000. (See table.)

Source: State of Play 2018

“[H]igher-income families spend hundreds to thousands of dollars each year to give their child a performance edge. Although unintentional, these expenses leave behind lower-income children,” the JAMA Pediatrics editorial writers pointed out.

“As the number of expensive, tryout-based leagues increase, recreational leagues become stigmatized as second rate… [and] community recreation leagues decline owing to less participation and investment.”

This dynamic is at a tipping point, they warn, and time to “level the playing field” is running out. Anxiety, depression and other chronic medical conditions are costly in their economic burden on society and in the diminished quality of life they inflict on their sufferers.

By comparison, the resources required to increase youth participation in sports are a bargain.

Resource: Visit The Sport Institute’s Exercise Rx, a search tool for healthcare providers and the general public to quickly find free and low-cost exercise resources in their own communities or online.