Concussion FAQs

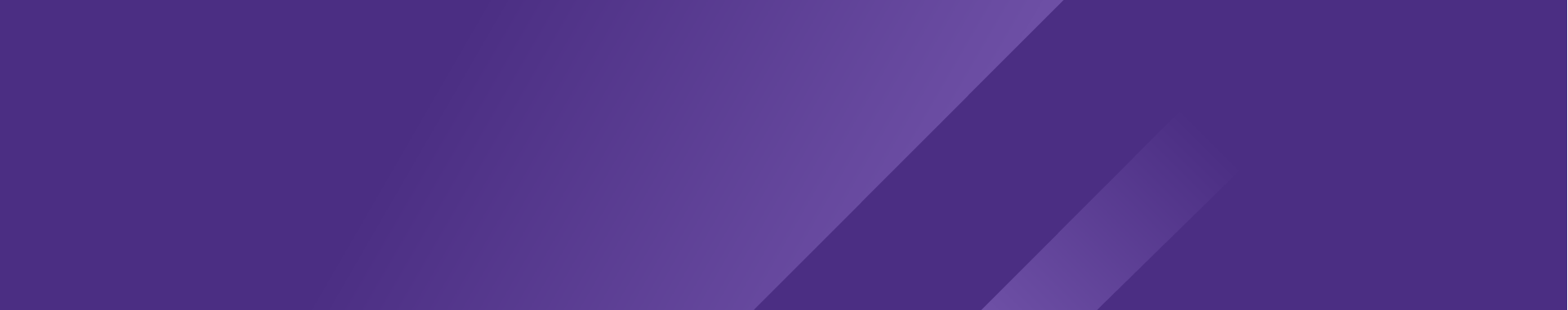

What activities cause the most concussions in young people?

A 2016 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that among children and adolescents with concussions, the activities most responsible for visits to hospital emergency departments were soccer among females and football among males. Young cyclists and basketball players were the next most likely to seek emergency care for concussions.

The report tallied total number of concussions (not rates) from each type of activity. As a result, it was not able to show which activities caused the most concussions per 1,000 kids participating in the activity. By that standard, lower-participation sports such as rugby, ice hockey or horseback riding would rank higher on the list.

Source: Coronado VG et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016

Can blood tests or imaging scans diagnose a concussion or detect recovery?

Blood tests and genetic tests can’t yet reliably diagnose a sports-related concussion or track the brain’s progress toward recovery. Imaging tests are usually not recommended for the same reason. Researchers continue to explore new technologies, but there is no perfect test.

If symptoms worsen or don’t improve as expected, a healthcare provider who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of concussions might recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). These imaging tests can identify dangerous conditions such as a skull fracture or bleeding in the brain (called a hematoma). But these situations are unusual and imaging is undertaken with caution, in part because CT scans expose athletes to potentially harmful radiation.

What is the chance that a youth athlete will have a concussion?

Scientific evidence on concussions in athletes younger than high-school age is scarce. No organized method exists for collecting data across age groups and sports. Despite these limitations, two studies shed some much-needed light on the risk of concussion in youth football. Together they suggest that up to five out of 100 youth athletes who play football for a full season may have a concussion.

In a 2015 study, researchers enrolled more than 3,000 football players ages five to 14 from 118 teams in six states. Athletic trainers attended each practice and game, and diagnosed the injuries. They documented players’ concussions during two seasons:

- Out of 100 youth athletes who played football for a full season, three had a concussion and 97 did not. The authors reported similar rates of concussion at all three levels of football—youth, high school and college.

In a more recent study, colleagues at the Seattle Children’s Hospital and The Sports Institute at UW Medicine followed 863 football players ages five to 14 for two years. Athletic trainers attended every game, and documented potential concussions.

- Out of 100 youth athletes who played football for a full season, five had a concussion and 95 did not.

A smaller study of 351 female middle-school soccer players reported a considerably higher rate of concussions. Over the course of four years, parents used a sideline symptom checklist to diagnose injuries and report them through an online surveillance system. Among these elite players, 13 out of 100 had a concussion each season. The researchers believe the rates reported in other studies may be artificially low because many athletes do not report concussion symptoms to their coaches or athletic trainers.

Sources: Chrisman 2018, Dompier 2015

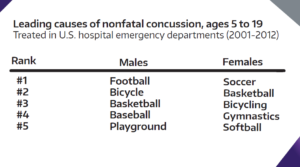

What is the chance that a high school or college athlete will have a concussion?

Reported rates of concussion in high school and college vary widely. Estimating the true risk is difficult. In part, that’s because definitions of concussion vary from place to place and methods of collecting data are uneven. It’s also because many concussions are never reported.

Researchers have conducted several large studies that examined concussion data in male and female athletes.

- Overall, out of every 100 athletes who played a sport for a full season, up to five had a concussion. On average, 95 or more did not have a concussion.

A large study of high school athletes in Michigan, for example, enrolled more than 190,000 boys and girls who played 15 sports.

- Out of every 100 athletes who played a sport for a full season, about two had a concussion and 98 did not.

- The sport with the highest rate was football, where about four in every 100 players had a concussion each season.

Another study looked at 32,156 college athletes who participated in 13 men’s and women’s sports.

- On average, about four out of 100 had a concussion and 96 did not.

- The rate of concussion in football was about 5 in 100. The rates of concussion in men’s and women’s ice hockey and men’s wrestling were a bit higher, up to 8 in 100.

- The lowest rates were in men’s baseball, women’s softball and men’s soccer.

Other studies have reported higher rates. For example, among high school athletes who play football or girls’ soccer for a full season, as many as 10 out of 100 have reported a concussion.

Sources: Bretzin 2018, Kerr 2017, McCrea 2013

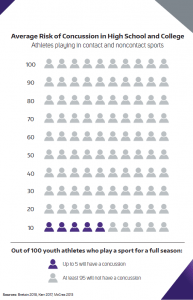

Which high school and college sports have the highest and lowest risk of concussion?

The rate of concussion in specific sports varies widely from study to study, so it is difficult to rank sports from highest risk to lowest with true precision.

Risk in men’s sports. Most research shows that the risk of concussion among men is highest in rugby, football, ice hockey, lacrosse, soccer and wrestling.

Risk in women’s sports. Among women, soccer, lacrosse, ice hockey and basketball usually have the highest rates of concussion.

In sports where men and women play the same game by similar rules (for example, soccer and basketball), women generally have a higher rate of reported concussions than men. This may have to do with differences in physical characteristics or playing styles. It is also possible that women simply are more likely to report their injuries. To the surprise of some, the risk of concussion among women soccer players appears to be similar to that of male football players.

In virtually every sport, the rate of concussions is substantially higher during competitions and games than during practice. But injuries in practice are just as serious and deserve the same amount of medical attention.

The table below provides a rough estimate of concussion risk across a variety of high school and college sports.

Concussion risk in high school and college sports

Sources: Zuckerman Am J Sports Med. 2015; Black Clin J Sport Med. 2016; Willigenburg Am J Sports Med. 2016; Graham IOM 2014; Marar Am J Sports Med 2012

Why do some people take longer to recover than others?

Although research shows that concussion symptoms go away within a week or two for most athletes, they sometimes take longer. The risk that recovery will take longer may be greater in athletes who:

- Had a greater number of symptoms at the time of their concussion (four or more)

- Had more severe symptoms at the time of concussion, such as loss of consciousness (blacked out) or amnesia (memory loss)

- Did not immediately report symptoms of a concussion and continued to play

- Had a previous concussion

- Had a recent concussion

Athletes ages 13 through high school may also take longer to recover than college-age athletes, especially if they have had more than one previous concussion.

And recovery may be more difficult for people with certain medical conditions that they had before their injury. These include migraine headaches, depression, anxiety or panic attacks, learning disabilities and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, although some recent research has raised questions about these risk factors.

Athletes in certain sports seem to be at greater risks of prolonged recovery. In one large, careful study:

- Lacrosse players had more than twice the risk of a long recovery compared to soccer or football players

- Ice hockey players had three times the risk of a long recovery

The current evidence suggests that male and female athletes are at similar risk for experiencing persistent symptoms and a prolonged recovery.

What should I do if the symptoms don’t go away?

A few athletes have symptoms that linger for weeks or months. In a study of high school and college athletes, about two out of every 100 athletes with concussions reported symptoms that lasted longer than one to three months.

Athletes with lasting symptoms report continued headaches, disturbed sleep, fatigue, slowed thinking and other problems. These can take a heavy emotional toll. Athletes may feel frustrated, irritable and restless.

If symptoms persist, athletes should seek help from a comprehensive concussion program or a healthcare provider who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of concussion. Healthcare providers who specialize in concussion management include:

- primary care sports medicine physicians

- physiatrists

- pediatricians with sports medicine training

- neuropsychologists

- neurosurgeons

- neurologists

Do helmets prevent concussions?

The short answer? No.

Helmets can prevent skull fractures, bleeding in the brain and other head and face injuries. But they can’t absorb the full force of a jolt that disrupts the brain and causes the many problems experienced by an athlete who has a concussion.

Do helmets lessen concussion severity? Research suggests that among athletes who have concussions, those who play sports with helmets and those who play without helmets have similar outcomes in the first few days after injury.

To the extent that helmets help, older helmets in good repair seem to offer the same level of protection as newer ones.

For further reading on concussion prevention, see Concussion Prevention: What Works, What Doesn’t