Myth: Specialize Early to Become an Elite Athlete

Mounting evidence challenges a deeply held conviction among youth sports participants that specializing in a single sport at a young age is critical to success.

Increasing numbers of parents, athletes and coaches believe that early specialization will provide athletes with a head start—that by focusing intensively on one sport year round, they’ll get better at it than other kids and achieve greater athletic success. With this will come social, economic and other benefits.

Meanwhile, doctors and other health professionals caution that early specialization can have a darker underside—that, compared to multi-sport athletes, young single-sport competitors are more likely to develop overuse injuries, suffer from stress and early burnout, or dropout out of sports altogether.

Is it necessary for young athletes to specialize in one sport to succeed in athletics later? The short answer: Probably not.

The allure of elite status

The American Academy of Pediatrics says early specialization occurs when an athlete focuses on a single sport at the exclusion of others, often year round, before reaching puberty. Although the AAP and other medical societies advise against early specialization, faith in its prowess continues to grow.

Examples abound. According to a 2018 survey, most youth club athletes believe that specialization will improve their performance and the chances of making both their high school team and a college team. They also believe specialization will increase the likelihood of receiving a college scholarship.

Similar prospects buoy the hopes of athletes’ parents. In a 2017 survey taken at a New York City sports medicine clinic, half of parents encouraged their children to specialize, and more than half believed their children would play in college or professionally.

Hopes at odds with reality

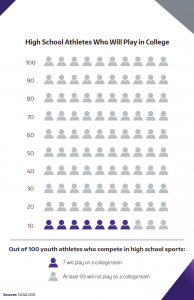

Unfortunately, athletes’ and parents’ expectations are vastly at odds with reality.

The math is fairly straightforward and unforgiving. There are close to 8 million athletes playing in high school. There are fewer than half a million slots for athletes on college teams. That means, on average, about seven out of 100 high school athletes make a college team. Perhaps one in 100 receives a scholarship. And even fewer make it to the Olympics or pros.

Despite the achievements of prodigies such as Tiger Woods and Mikaela Shiffrin, there is surprisingly scant evidence that the majority of athletes who achieve elite status do so because they specialized at an early age. Indeed, most of the evidence supports the contrary view.

Source: NCAA 2018

Most elite athletes did not specialize in their youth

Data collected over the past few years—including the first studies in professional athletes—suggest that early specialization is not necessary to achieve elite levels of performance. Compared to other athletes, athletes competing at the highest levels more often postpone specialization until later in adolescence and compete in more sports during high school.

- Professional football: According to Tracking Football, a scouting service that keeps tabs on high school and college athletes, 88% of NFL draft picks in 2018 and 2017 were multisport athletes in high school. (The other sports most often played by football players were track and field and basketball.)

- Professional hockey: In a 2019 survey of professional and college ice hockey players, the average age of specialization was 14. “Early pediatric sports specialization before age 12 years is not necessary for athletic success in professional and collegiate ice hockey,” the Penn State authors concluded. (Other sports most often played by hockey players were soccer, baseball and lacrosse.)

- Professional basketball: Although it isn’t clear when professional basketball players begin to specialize, most focused exclusively on basketball by the time they reach high school. Those who played additional sports in high school seem to better endure the rigors of the NBA. Compared to their single-sport teammates, NBA first-round draft picks who were multisport athletes suffered fewer major injuries in the NBA, played in more games and had longer careers.

- NCAA Division I: Several studies have shown that Division I athletes usually played multiple sports as children, and specialized later. “Across a large variety of sports, only a minority of Division I collegiate athletes specialized in a single sport as an early adolescent,” noted Columbia University researchers in a 2019 paper.

- International. Danish researchers looked at characteristics that might differentiate elite competitors from non-elite athletes in international sports. Both groups of athletes played multiple sports. However, near-elite athletes devoted more time to training in their main sport when they were younger, before age 15. The elite athletes ramped up training in their main sport after age 18. “The optimal career path is not only a question of amount of training hours but also a question of when training regimes occur,” the Danish researchers concluded.

Free play and pickup games

The AAP points out that early specialization programs may leave little time for the free play or pickup games that kids do just for fun, without reward. And they have the potential to harm children’s health in numerous ways.

Whether early sports diversification is the reason some kids become better athletes over the long run is unknown, but it doesn’t appear to be a barrier. Waiting and specializing later seem to work fine.